By Lisa Cox, Public Information Officer for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, San Diego National Wildlife Refuge Complex

If you’ve heard of clapper rails, you may know they are not very agile fliers and tend to quietly prod around within the coastal salt marsh where they were born, or released into.

But the endangered Light-footed Ridgway’s Rail (Rallus obsoletus levipes) in Southern California and Baja California is not so much of a “home body” as originally thought. We now have ample proof that rails can also move between wetlands, with one bird travelling a whopping 160 miles.

If you give the rail a chance, it will establish new territories in supportive habitat. So how do you give the rail a chance, when over 90% of its habitat has been destroyed?

Restore intertidal salt marsh. Protect those marshes from human mediated disturbance and work to ensure the species retains enough genetic diversity to persist and thrive into an uncertain future.

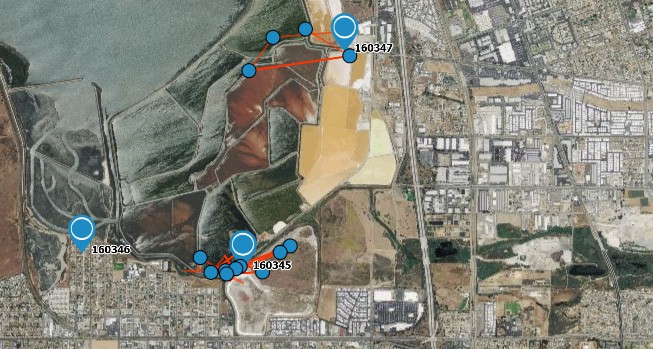

At the San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge, six rails that were bred in a zoological breeding program were released in September 2016 into a newly restored salt marsh in the southwest corner of San Diego Bay. They’ve since settled into 3 different territories on the refuge. These rails were fitted with satellite telemetry to allow them to be tracked.

In the past year, biologists have seen some interesting movements of the three remaining rails. One of the birds traveled 2.5 miles north before it was found perished of unknown causes. One rail, with band number 160346 established itself in the southeast corner of the former salt Pond number 10, the area that was restored in 2011. Rail 160345 moved east along the Otay River, and Rail 160347 moved about 1.4 miles northeast and settled within a tidal channel surrounded by the still-functioning salt pond system.

The subspecies’ northern most range is at Point Mugu Naval Base in Ventura County, California, where captive-bred rails were released between 2002 and 2008. Although some of them stayed, other rails dispersed. For example, a female banded 1035-8878 bred at the Living Coast Discovery Center was released into Point Mugu on August 28, 2004. 160 days later and over 90 miles distant, she was photographed in Upper Newport Bay. This shattered the previous long-distance movement of 13.5 miles recorded by avian biologist Dr. Richard Zembal in the early 1980s.

Another long distance traveler was a rail released at Seal Beach National Wildlife Refuge found deceased in the city of Fillmore, Ventura County, in October 2015 two weeks after his release. That’s 75 miles as the crow flies, but over 100 miles if the bird followed the coastline up through Los Angeles, Ventura, and then east up the Santa Clara River.

But the longest distance record has now been set by female 1065-39863. Nicknamed “Amelia” after Amelia Earhart, she traveled 160 miles from her release location at Point Mugu in August 2009, back to her hatching site in an enclosure at Sweetwater Marsh, San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge in November 2010. Navigating through the heavily industrialized urban coastal areas of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and San Diego, seeking pockets of remnant salt marshes along the way, Amelia followed her instincts back to the place right where she hatched. She was found interacting with a male rail through the cages at the Living Coast Discovery Center where she hatched, 1 year and 2 months earlier. An incredibly unique opportunity presenting itself, biologists paired her with that male where they became one of the most productive pairs within the program, producing 24 chicks that were also released into the wild.

When Amelia was a few years older, she was released into Sweetwater Marsh, where she could be wild once again. She was re-sighted in the company of a wild-bred rail in that marsh in July 2015, showing the world that she and her species can be survivors.

The captive breeding program Amelia was a part of is a successful nearly 20-year partnership between several organizations dubbed “Team Clapper Rail.” The San Diego Zoo Safari Park, SeaWorld San Diego, and the Living Coast Discovery Center (previously called the Chula Vista Nature Center) function as breeding grounds, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s San Diego Bay National Wildlife Refuge serves as proving grounds to get the birds ready for release. The California Department of Fish & Wildlife is also a major partner.

Because of the team’s efforts along with continued conservation and restoration of salt marshes throughout southern California since 2001 the U.S. population of the rails has more than doubled, now numbering an estimated 656 pairs between Point Mugu in the north, south to Tijuana Estuary at the US/Mexico border. But the species isn’t out of the woods yet.

The southernmost range of the Ridgway’s rail is south of Ensenada in Baja California, Mexico where the rails are mostly concentrated in Bahiá San Quintín. This bay is protected by the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP), and for good reason. According to a thesis by Marco Antonio Gonzalez Bernal in 2009, Bahiá San Quintín had an estimated population of 661 individuals. Unfortunately this estimate indicated a reduction in the population of possibly 56% compared to estimates made in the 1980’s.

This bay is the largest coastal wetland of northern Baja California. Similar to the United States, coastal salt marshes in Baja are under pressure from human development with habitat impacts including goat grazing, roads through the marsh, human disturbance, feral dogs and cats, agriculture encroachment into the salt marsh, desalination plants and aquaculture facilities.

Bahiá San Quintín has also been identified as a Priority Terrestrial Region by the Mexican National Biodiversity Commission, a Globally Important Bird Area, a Center of Plant Diversity by the World Wide Fund for Nature, and a Site of Regional Importance by the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network. Moreover, in 2008 the bay’s lagoon complex was declared as Wetlands of International Importance by the Ramsar Convention.

Clearly, the marsh lands in Baja are incredibly important to protect. However that future is uncertain, and additional studies will need to be conducted throughout the range of the species.

It is the hope of Team Clapper Rail to join forces once again with their Mexican partners and bolster the population of rails throughout their range to ensure an eventual self-sustaining population.