By Jennie Duberstein, Casey Setash, and David Molina

What do you think of when you hear the name “Sonoran Joint Venture”? Do images of saguaros and roadrunners fill your head? You may not immediately think of waterfowl and wetlands.

So you might be surprised to learn that there are nearly 3,500 miles of coastline in northwest Mexico and southern California. Combined with a number of large and important wetlands in the interior of the SJV region (including the Salton Sea, Colorado River, Imperial and Mexicali Valleys, San Jacinto Wetlands, and Willcox Playa), the region provides wintering habitat for a vast number of waterfowl, primarily from the Intermountain West and Pacific Flyway.

In fact, over 80% of Pacific Black Brant winter on the coasts of the Baja peninsula and mainland Mexico. Seventy percent of Pacific Flyway Redheads winter in Mexico, mostly along the coasts of Sonora, Sinaloa, and Baja California. More than 25,000 Snow and Ross’s geese and over 50% of the Pacific Flyway’s Ruddy Ducks winter on the Salton Sea in southern California. And the coast of Sinaloa alone supports nearly 25% of the entire country of Mexico’s wintering waterfowl population.

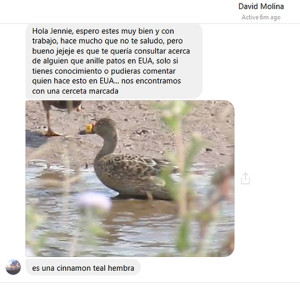

On January 25, 2017 I was at home working on my computer when I heard the familiar “ding” of Facebook notifying me that I’d received a message. I clicked over to see that David Molina, a biologist and SJV partner from Nayarit, Mexico, had sent me a note.

On January 25, 2017 I was at home working on my computer when I heard the familiar “ding” of Facebook notifying me that I’d received a message. I clicked over to see that David Molina, a biologist and SJV partner from Nayarit, Mexico, had sent me a note.

David’s career is dedicated to wildlife monitoring, conservation, and research, with a special focus on the birds of Nayarit. Since 2009 he has been undertaking research and monitoring of aquatic birds in Marismas Nacionales, Nayarit, one of the largest and most important wetland complexes for migratory birds in northwest Mexico.

David currently works as an independent field biologist, where helps coordinate a MoSI banding station in the Sierra de San Juan State Biosphere Reserve. As part of this work David conducts monitoring of breeding birds, counts and differential response of birds to impacts, and documenting species richness.

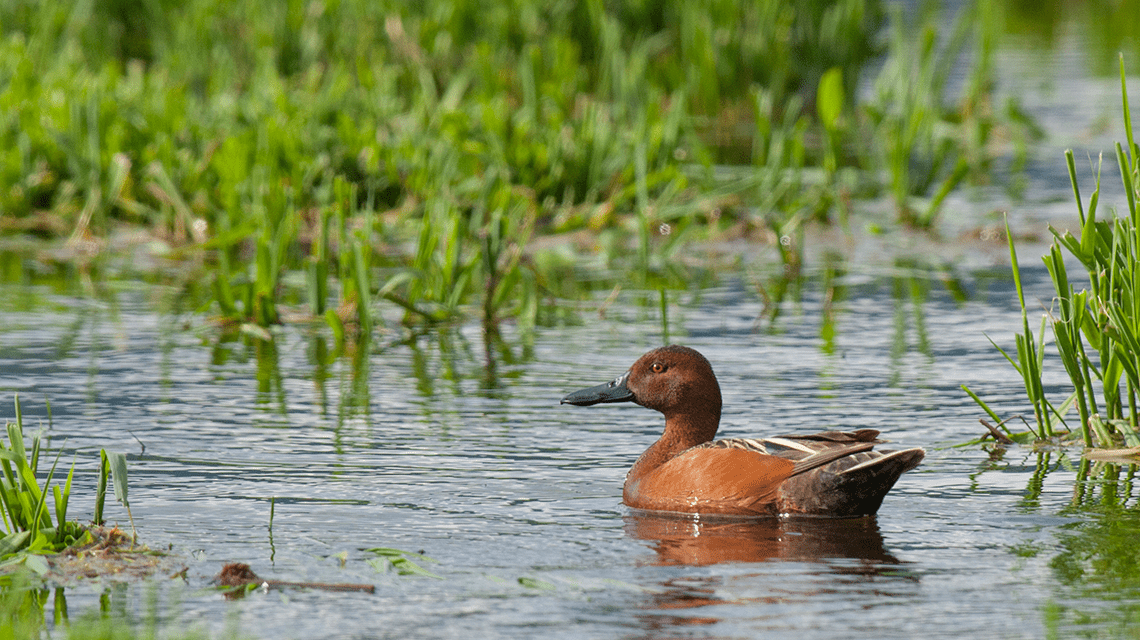

One morning in January David was conducting waterbird surveys near a small temporal lagoon alongside an irrigation canal that was under construction, when he spotted something out of the ordinary: a female Cinnamon Teal marked with nasal discs.

“It was a surprising observation,” he said. “I was in the field and saw something unusual,” he wrote. “Do you know anyone in the United States who is banding ducks?” Attached to the message was a grainy image of the teal in question.

I sent a message to the FWS Migratory Bird Program regional offices in Albuquerque and Denver, and before an hour had passed we had an answer.

Casey Setash, a graduate student at Colorado State University, has been conducting research on waterfowl in the Intermountain West for the last several years with a specific focus on Cinnamon Teal breeding ecology. Setash, with field assistance from Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuge in southern Colorado, has been marking Cinnamon Teal with nasal discs since 2015 in an attempt to determine their breeding site fidelity, wintering habitat use, and survival throughout their annual cycle. In addition to marking birds, she is finding and monitoring Cinnamon Teal nests and tracking broods via radio telemetry to estimate nest and duckling survival during the breeding season. Given the increasing aridity and competition for water throughout the Intermountain West, ascertaining a better understanding of what drives Cinnamon Teal production and how they fare in a drier climate will be extremely important in the coming decades. Birds banded on Monte Vista NWR since 2012 have been re-sighted by birders and hunters all over North and Central America, from eastern Washington to Nicaragua, providing new insight into the migration ecology of cinnamon teal.

The bird spotted by David Molina was one of over 100 birds that Setash marked with nasal discs. Sightings like these are pivotal in acquiring a more thorough understanding of this enigmatic species. It travelled approximately 1,500 miles between its breeding grounds in southern Colorado and its wintering grounds in northwest Mexico, the temporal wetland where David found it, near the village of Estación Yago, northwest of Tepic in Nayarit.

David’s discovery of this bird was not his first such connection between the western U.S. and northwest Mexico. In the summer of 2014 Javier Paniagua Herrera, another wildlife biologist from Nayarit and a colleague of David’s, traveled to Salt Lake City, Utah, where he worked with Dr. John Cavitt, a zoology professor at Weber State University. Together, they put satellite transmitters on a pair of American Avocets. In the winter of 2014-2015 the researchers were able to follow the signals and saw that one of the birds spent the winter in Marismas Nacionales, although they weren’t able to get a visual documentation. But in December 2015 the signal showed that the bird had again returned to the area, and this time Javier and David were lucky enough to get a photograph of the bird—a male. David writes that they have also observed Snowy Plovers that were banded in Utah and migrate to Marismas Nacionales every winter.

These observations clearly show the migratory connection between aquatic bird populations in the western United States and permanent and temporal wetlands in northwest Mexico. They also show the importance of working across borders to conserve birds at all points in their annual cycle, from breeding to migration to wintering. Programs like the Sonoran Joint Venture help bring together diverse partners to bridge gaps in communication and capacity and help make connections to work on bird and habitat conservation at these larger scales.

If you spot a marked Cinnamon Teal, please report your sightings to David Olson or Casey Setash. One thing is certain: we’ll be keeping our eyes open for marked birds the next time we’re in the field!

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dan Collins, Dave Olson, Brian Smith, and Casey Stemler for helping to connect the dots in this conservation story.