By Alberto Macías Duarte, Research Professor, Universidad Estatal de Sonora

The Aplomado Falcon (Falco femoralis) is a colorful raptor that inhabits tracts of Chihuahuan desert grasslands in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The species’ geographic distribution is extensive, comprising of savannah-like habitats along the U.S.-Mexico borderlands southward into Central America and throughout South America. The northern Aplomado Falcon (Falco femoralis septentrionalis) was listed as an endangered species in the United States in 1986. This designation was in response to severe eggshell thinning and pesticide contamination in falcon populations from eastern Mexico. At that time, the eastern Mexico (mainly Veracruz) population was the closest native Aplomado Falcon population to the United States since the species extirpation more than 30 years before.

The natural history of Aplomado Falcons is unique among raptors and important in addressing basic ecological and evolutionary questions. Aplomado Falcons prey almost exclusively upon birds. They show inverse sexual dimorphism in body size, i.e., females are noticeable larger than males. They also hunt cooperatively in pairs, which significantly increases hunting success. Females almost invariably lay 3 eggs per clutch as opposed to other falcon species, and both males and females incubate the eggs. Unlike other falcon species, their nestlings hatch with a grayish-dusky natal down, not the typical white color. Same as other Falco species, they do not build their own nest. Aplomado’s depend on nest structures built by other large birds such as ravens and hawks.

In the mid 1990’s, a native population was discovered in Chihuahua, Mexico, where as many as 35 pairs were possibly breeding at a single year. This population brought some hope for the restoration of the species in the Chihuahuan desert of the United States. An extensive demographic study was conducted by USFWS, The Peregrine Fund, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua and PROFAUNA. The study delineated two core breeding areas in eastern/central Chihuahua; Sueco and Tinaja Verde (municipalities of Chihuahua, Ahumada and Coyame) seemed to contain the majority of the Aplomado Falcon breeding habitat in northern Mexico. However, a new threat appeared in 2006 when the creation and development of agricultural colonies began an extensive conversion of occupied falcon habitat into almost 70,000 ha of irrigated farmland in Sueco. Currently, only four of 24 former breeding territories have not been farmed in Sueco. The extirpation of the Aplomado Falcon in Chihuahua in the coming decades is imminent.

The question that arises now is whether there is enough suitable breeding habitat remaining to sustain a population given: 1) the extensive destruction of breeding habitat in Chihuahua by agriculture and 2) the failure of a reintroduction program using captive-bred falcons to restore the breeding population in the Chihuahuan desert of New Mexico and west Texas. Some people believe that there is habitat available that has not been explored in surviving patches of desert grasslands in northeastern Aguascalientes, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, western San Luis Potosí, and Sonora, as well as in Arizona, New Mexico and West Texas. The problem with this assertion is that there has been intense ornithological work in those grasslands in the last decade and few falcons have been reported there.

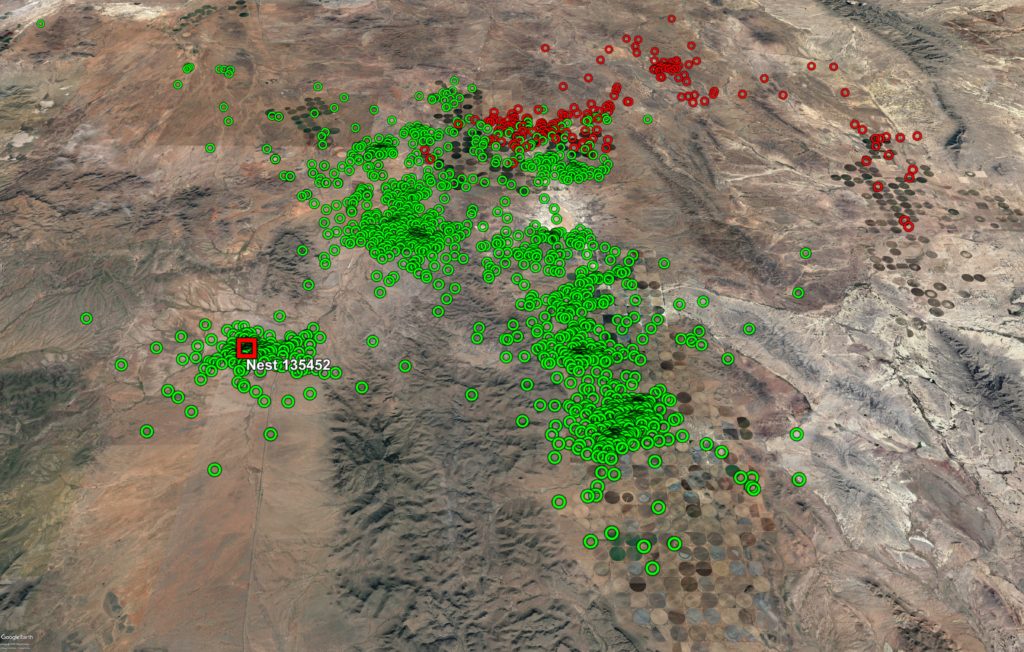

To shed some light into answering the question of how much habitat is still available for Aplomado Falcons, Universidad Estatal de Sonora deployed 3 Argos satellite transmitters on 3 fledglings (2 males and 1 female) in May of 2015 in Chihuahua. The purpose of the study was to see if exploratory movements by birds during their natal dispersal (movement from their birthplace to the location of first reproduction) would potentially reveal new tracts of breeding habitat besides those identified by the original demographic study. This study also aimed to determine the fate of young birds. It has been puzzling to researchers that after almost 20 years of banding hundreds of falcon nestlings, only one banded bird has been confirmed recruited into the breeding population.

Despite the small sample size, the study yielded some interesting results. One of the young males had transmissions for one week around its natal territory and then disappeared. His two siblings’ carcasses were found, probably depredated by coyotes, but it was not possible to find the tagged falcon nor its transmitter. The young female’s transmitter yielded positions for over a year. This female moved over 300km from her natal territory, but transmissions ended within the known core breeding areas, about 100km from where she originated. The other young male is still transmitting a signal after three years. After moving back and forth distances as far as 100km in a couple of days, this falcon found a mate and nested during its third year in a vacant breeding territory at Sueco, just 15km from its birthplace. The latter two falcons dispersed from their natal territory about 100 days after fledgling. They wandered around other breeding territories (delineated by the long-term demographic study) that were either intact, or converted to farmland. The falcons occasionally explored areas outside the core breeding areas, only to reveal potential breeding habitat being converted to farmland. Our telemetry data suggest that suitable Aplomado Falcon breeding habitat, in spite of its apparent regional availability, is actually limited to central Chihuahua and its current rate of loss seriously limits the potential recovery of the species in the Chihuahuan Desert.