By Robert Murphy, USFWS Southwest Region

Protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, western North America’s Golden Eagles are increasingly threatened by multiple factors such as collision with wind turbines, electrocution on power lines, and lead poisoning (from eating carcasses left by hunters who used lead ammunition). The cumulative impact on eagle populations is unclear, however, because we are missing basic knowledge about population dynamics, such as survival rate. We do know causes of mortality, but the relative importance of these remains unknown. We also need to improve our understanding of movement within and among populations of Golden Eagles. In order to make good management decisions for Golden Eagles, we need to address these knowledge gaps.

In 2010, the Migratory Birds Division of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Southwest Region partnered with the Jicarilla Apache Nation, Navajo Nation, Southern Ute Tribe, and U.S. Bureau of Land Management to document survival, causes of mortality, and ranging behavior of Golden Eagles, focusing on eagles from the Four Corners area at the heart of BCR 16. Eagles are fitted with “PTT” satellite transmitters just before fledging from their nests. PTTs currently in use weigh only 1.5 ounces and operate for at least 3 years. During most of the day, PTTs provide hourly locations accurate to within 50 to 75 feet. Biologists closely monitor eagle movements via satellite data so that they can respond quickly to find an eagle if lack of movement suggests death or injury. We will reach a project goal of tagging at least 50 young eagles with PTTs in the coming months. Eagles tagged in 2010 will reach adult age (five years) by spring 2014. Several adult eagles also have been tagged on their breeding territories to gather information about adult survival.

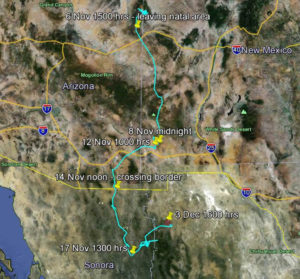

Yearly mortality of the eagles, excluding adults, has averaged about 40%, a relatively high level. Mortality during the months after fledging has been high, due mostly to starvation; most of the region is in severe drought and rabbits and other prey are scarce. Unusual losses included one juvenile eagle that drowned in a steep-sided pool, naturally carved in sandstone. Another was killed by a mountain lion at a deer carcass. Most eagles have remained within 100 miles of their nest of origin, often after wandering for weeks up to 1000 miles away. One juvenile bird that was captured and tagged on the Navajo Nation then traveled into Sonora and Chihuahua, which is the southernmost movement of a juvenile originating in the Four Corners area.

A notable pattern emerging is that non-breeding Golden Eagles from the Four Corners region reside in more northerly places, especially Wyoming, during late spring through early to late fall. Some also have remained at elevations of 10,000-13,000 feet for several weeks or months during summer.

Although 2013 is likely the last year that eagles will be tagged, the tagged eagles will be followed until they die or their PTTs quit functioning, some possibly into the 2020s. Researchers in other western regions are undertaking similar efforts provide a comprehensive picture of the Golden Eagle’s ecology and solidly support population management decisions.