By Eduardo Palacios, Research Scientist at Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE)

The coastal wetlands of northwestern Mexico are some of the most important habitat for migratory waterbirds that winter in Mexico. It is vital to determine what are the threats and disturbances that this group of birds and their habitats face in order to conserve not only the migratory birds, but also other resident species that share these habitats. By monitoring focal species, we can make informed management decisions to that guide conservation actions.

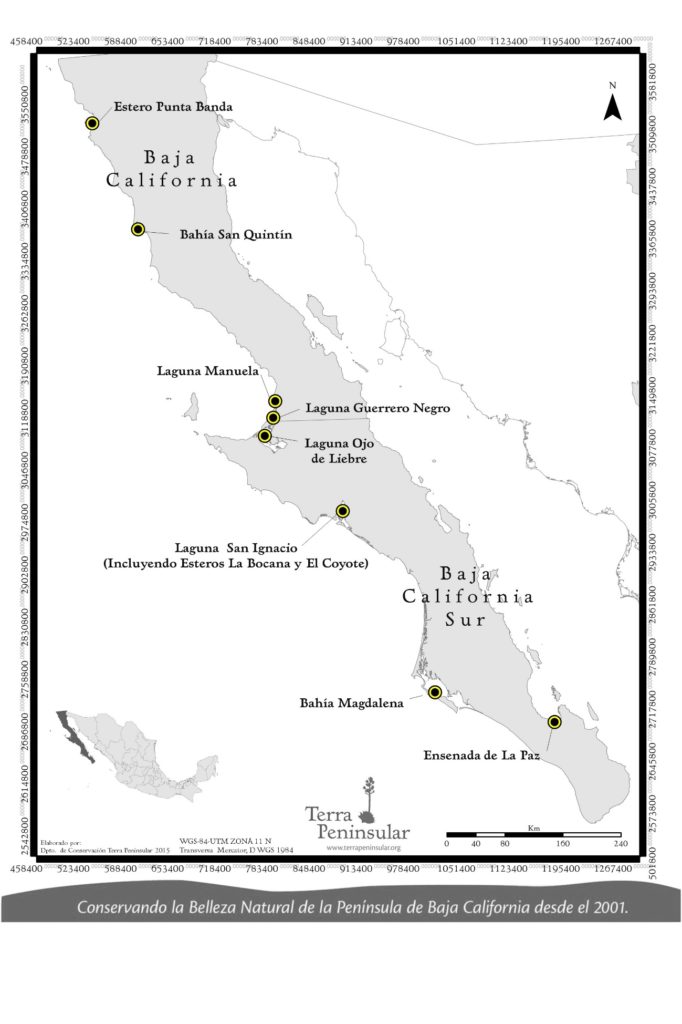

In the spring of 2017, in Ensenada, B.C. with funding support from the Sonoran Joint Venture’s Awards Program, Terra Peninsular in collaboration with CICESE, the Grupo Aves del Noroeste (GANO), and Point Blue Conservation Science conducted a workshop with experts and site leaders to develop a standardized monitoring protocol for migratory waterbirds and their habitats. This protocol focused on 13 priority coastal wetlands in northwestern Mexico for migratory waterbirds (not including ducks and geese), that also sustain important populations of at least one of four designated focal species for the program (American White Pelican, Brown Pelican, Forster’s Tern, and Black Skimmer). While regionally focused, this Coordinated Bird Monitoring protocol could be implemented in other coastal or inland wetlands of Mexico, as well as for other species dependent on wetlands. In addition, it is compatible with other monitoring protocols in northern and southern Mexico.

The monitoring protocol allows land managers to 1) standardize waterbird counts and habitat monitoring, 2) evaluate local habitat conditions and quantify the use of wetlands by waterbirds during non-breeding periods, 3) collect data on waterbirds and their habitats at local scale (e.g. San Quintín Bay) that can be used to generate descriptive summaries and/or analyzed at larger spatial scales (e.g. Peninsula of Baja California, northwestern Mexico, and migratory corridors), 4) use adaptive management of resources and adjust conservation actions as more information is generated on the responses of waterfowl to the specific management measures that are implemented in a site, and 5) document and address threats that occur at the conservation site.

The project was first carried out during mid-winter from December 15, 2017 to January 31, 2018 at sites designated as priority waterbird habitat that also included one or more of the four focal species. Surveyors completed an area count at the selected sites, in addition to collecting specific habitat information. GANO is a coordinated network of more than 50 volunteers and professional biologists from 13 institutions. They led the implementation of this monitoring program. One leader per region coordinated with the local site leaders and teams of observers. If the program expands to more regions of Mexico in the future, there will need to be a national coordinator who will work closely with the regional coordinators to facilitate the program.

This monitoring program built off the Migratory Shorebird Project, another coordinated bird-monitoring program. Since 2015, data for both of these projects are stored in the California Avian Data Center (CADC), a node of the Avian Knowledge Network that is hosted by Point Blue Conservation Science. The data is captured through an online portal with English and Spanish versions. Raw information is and will be available upon request.

Next steps of the project will be to evaluate population trends and spatial distribution in relation to changes in habitat, disturbances, climate change and other limiting factors for these species. It is hoped that the managers of the natural areas and scientists will collaborate to continue developing and fine-tuning the monitoring protocols and databases in order to make informed decisions about waterbird and habitat management at multiple spatial scales.

The management plans of the priority areas in the region will benefit from this monitoring program, since it will be an important resource that the directors and staff of each Protected Natural Area will have to make management decisions and evaluate the effectiveness of the actions of management that are implemented in each area. This monitoring program should help a site administrator decide for example which species to manage in a given site; how important is that individual site on the global scale; how they could coordinate with other managers in the region so birds have sufficient and good quality habitat, and at the right time and place.