Corrie Borgman, Landbird Biologist, USFWS, Division of Migratory Birds

As a major focus of the Sonoran Joint Venture, we are excited to share some updates about region-wide Desert Thrasher efforts. Two species, the LeConte’s and Bendire’s Thrashers are endemic to the deserts of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico and are indeed the focus of much attention. Even still, scarce, and cryptic, these birds fly under our radars, unnoticed but by those specifically looking. The pressures that these arid-dwelling birds face still exist, and aside from increased attention from those that may manage the lands they are commonly found within, we still face challenges to achieving conservation. However, due to much collaboration and communication, we make headway in the face of these challenges.

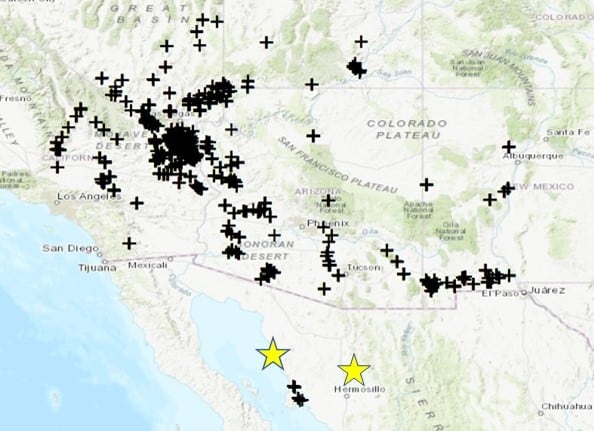

The Desert Thrasher Working Group (DTWG) has continued to grow since its inception in 2010, and enlists biologists from agencies, universities, non-governmental organizations, and more, to fill information gaps, to identify threats, and to imagine solutions. These brown birds of brown habitats don’t make filling information gaps easy, and have proven to have low and periodic detectability, but the DTWG has now conducted surveys for both species across all five US states where they occur, and in Sonora, Mexico. We have learned much about habitat characteristics across the deserts of North America, though this learning has naturally led to more questions. For one, we now realize how different habitats can be from one desert to the next; not just in terms of plant composition, which is expected, but also structurally. Surveys in Mexico have revealed more Bendire’s Thrasher detections than the sum of what previously existed, but surveys failed to drum up the same for LeConte’s Thrasher detections. Yet both help tell a story about these Thrashers, and about their distributions past and present. They have also importantly engaged new partners across both countries. In addition to these survey results from Mexico, more years of surveys in the US are being used to update species distribution modeling efforts. Upon these results, the DTWG can evaluate where to focus surveys on in the future or expand the focus using surveys to answer questions needed to evaluate threats or other management questions.

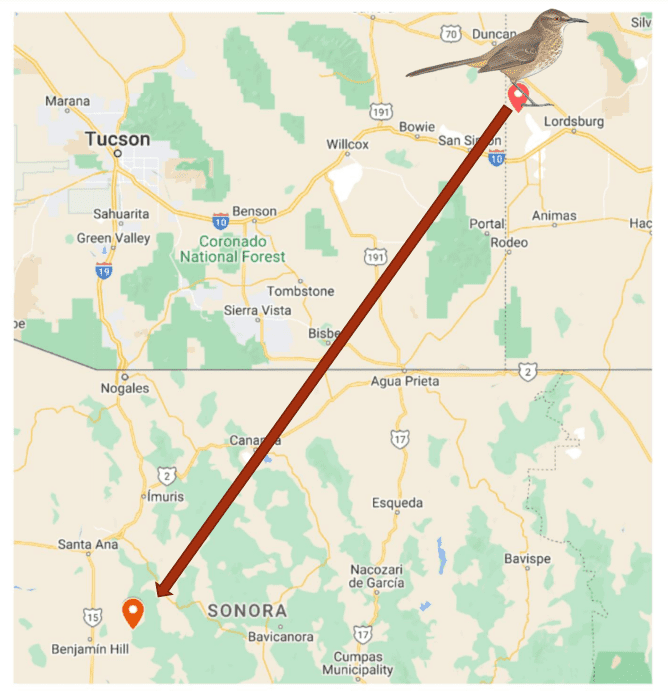

Another information gap that the DTWG has been working to fill is that of their migratory behaviors. Partners kicked off a pilot study in 2019 to track Bendire’s Thrasher movements using GPS technology. Since that time, we have learned about migratory behavior of different populations and are poised to learn more this spring. Birds that we were able to tag and recover in the Phoenix and Tucson areas in Arizona showed that not only did birds stay locally throughout the winter, but also remained on the same territories that they occupied during the breeding season. While this didn’t lead to exciting information about exotic wintering locales, it did show us that occupied Bendire’s Thrasher territories are important throughout the year. Since that pilot season, we have deployed another 45 GPS tags at sites in southwestern and central New Mexico (New Mexico’s “Bootheel” and the Sierra Ladrones), and in central and northwestern Arizona (Hassayampa Plains and Joshua Tree IBA). Which of these populations will exhibit migratory behaviors, and where might these birds end up? A teaser of tags retrieved in spring of 2022 show interesting movements (or lack of movements). Three birds trapped at the same breeding site in New Mexico’s bootheel moved between 0 and 320 km; staying either on their breeding territory throughout the winter, or moving as far as the western slopes of the Sierra Madre Occidental, near Benjamín Hill, Sonora. What patterns will the rest of the tags tell us from this and other sites? Are there any common wintering sites that may be used? Biologists are anxiously gearing up to recover tags beginning in March, 2023 to hopefully answer some of these questions.

As the DTWG continues to better understand the needs of these species, we are lucky to have dedicated engagement from so many partners. If you are interested in joining, please contact Corrie Borgman. Additionally, the DTWG will meet in person in conjunction with the Partners in Flight Western Working Group meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada, April 24-25, 2023 (WWG Meeting continues through April 28). Please join us if you can!