By Antonio Cantú¹ and Patrick Donnelly², ¹Harte Research Institute, Texas A&M University Corpus Christi, Corpus Christi, TX, ²Intermountain West Joint Venture, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Missoula, MT

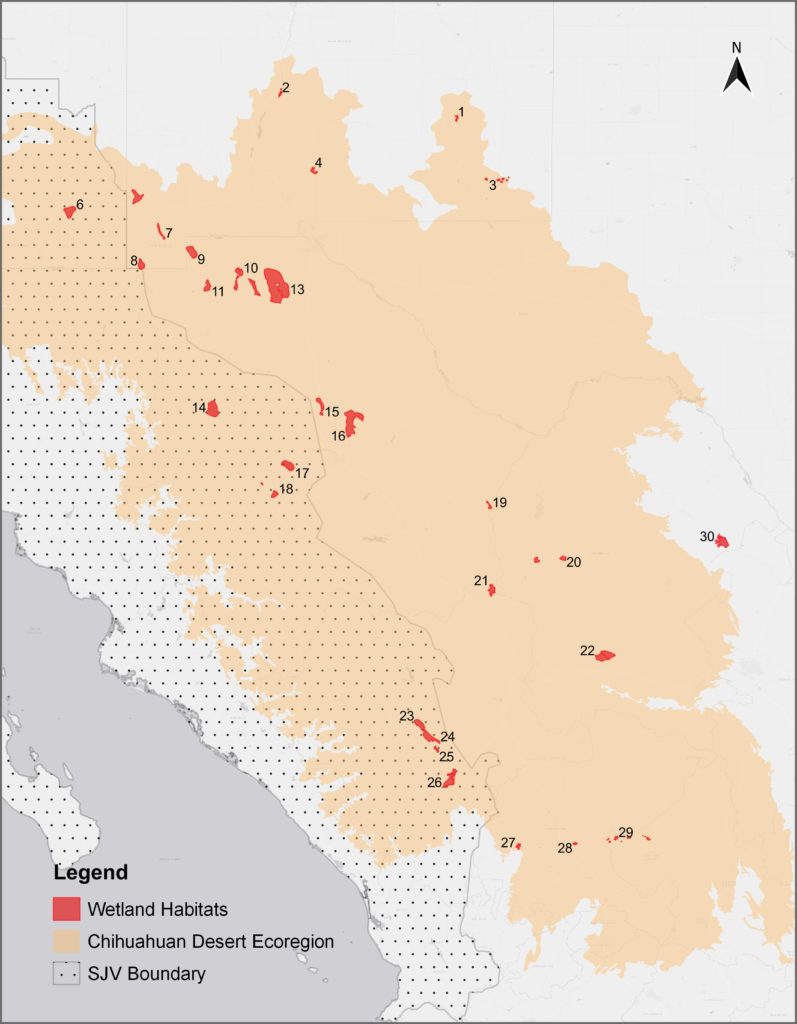

Wetlands within the Chihuahuan Desert play an important role sustaining migratory connectivity for North American waterbirds, providing areas to re-fuel and rest during their journeys between breeding and wintering grounds. Importantly, the timing and availability of water is key to provide habitat needs for these long-distance travelers. Without these resources, the increase in energetic cost of migration can have severe effects on the survivorship of migratory birds and impact their populations. A landscape perspective of how surface water availability changes spatially and temporally can not only help us understand which areas are more likely to be utilized by birds, but it also helps us identify areas of greater restoration or protection needs. To address these needs, we are evaluating inundation dynamics across historically important wetlands for migratory birds in the Chihuahuan Desert (Figure 1) to identify current drivers of habitat availability and monitor habitat trends to guide regional conservation planning and restoration efforts.

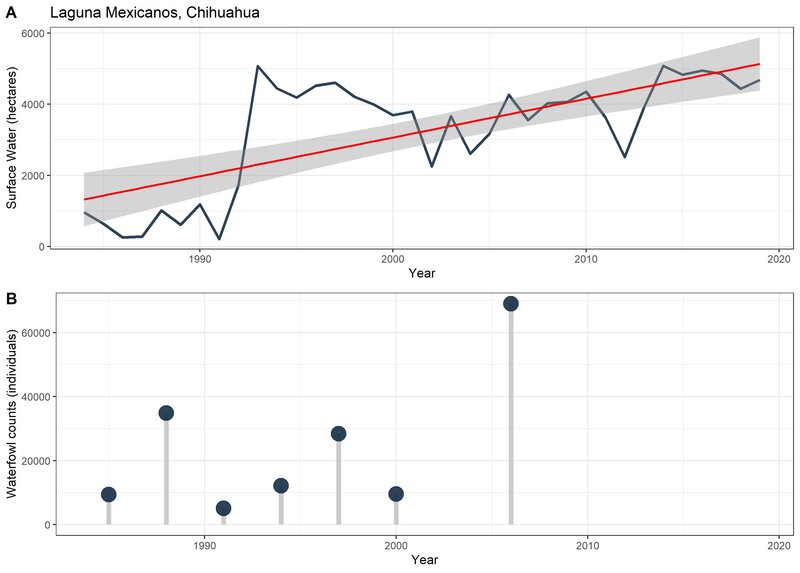

Most wetlands in the Chihuahuan Desert occur in closed basins that depend on summer monsoons for water. This characteristic delivers some degree of hydrological independence between wetlands at the regional scale, meaning that at a given time, a wetland within a basin may be flooded while the neighboring basin may be dry. Thus, regionally, we would find wetlands under different flooding regimes (wet, dry, partially flooded, etc.) in a particular year, which can translate to a diversity of habitats that support wide groups of species with different water level requirements (e.g., shorebirds, waterfowl, waders, divers). Wet and dry cycles are essential to sustain wetland productivity and structure. Historically, only a few sites would hold water during droughts, while wetlands would rebound during wet years at a regional scale, driving changing waterbird distributions over time (Figure 2).

Human-impacts and increasing climatic uncertainty are changing the natural dynamics of wetlands and influencing the extent (wetland area) and/or timing of inundation, which potentially results in mismatches between bird migration (species phenology) and habitat availability. Recent studies have identified significant wetlands declines in some regions within the Pacific and Central flyways, (see Haig et al. 2019), while habitats in the southwestern US and northern Mexico show greater stability, and in some cases expanding wetland availability (see Donnelly et al. 2020). This suggest that wetlands within arid regions surrounding the US-Mexico border may play an even greater role in sustaining migratory connectivity than previously thought.

Our preliminary results support this claim suggesting that collectively wetlands in the Chihuahuan Desert have remained hydrologically consistent over the last 35 years (1984-2019). Moreover, climate data for this same period indicates that evapotranspiration is the most important driver of annual surface water variability, indicating that the water balance of these wetlands has largely been maintained over time, as outflows in closed basin systems can only naturally occur through groundwater recharge and evapotranspiration. Individually, some sites show water declines (e.g., Willcox playa, Arizona and Encinillas, Chihuahua) highlighting a need for conservation and monitoring efforts, yet other sites show increasing resiliency (e.g., Santa Ana, Zacatecas and Laguna Mexicanos, Chihuahua), which may benefit from protection efforts.

The life cycle of migratory waterbirds is inextricably linked to the availability of habitats throughout their flyways. Their conservation, restoration, and protection require cooperative efforts among NGO’s, governments, landowners, and scientists across political and non-political boundaries of all levels. We are working to provide tools that can better guide wetland conservation for migratory birds and people in the Chihuahuan Desert and beyond, based on quantitative approaches to landscape connectivity structure and drivers of habitat change. We welcome the opportunity to discuss ideas and/or further collaborate in related topics. To learn more about this and other similar projects, please contact us!